The Edna textile mill, owned by Willis Benton Pipkin, was incorporated in 1889 in Reidsville, North Carolina. Mill houses surrounding the mill date back to 1901. Mills began to spring up throughout the South in the aftermath of the economic troubles from the Civil War and Reconstruction that forced many small, subsistence farmers off their farms in search of steady income. Mills often provided houses for its employees, “conveniently” located just feet away from the mill, which led to the formation of mill villages. The homes in the area surrounding the mill in Reidsville became known as the “mill vill” (for mill villages) or “mill hill” (for its geography). Mills were usually located next to rivers (for power) or railroads (for easy importation of unfinished goods and exportation of the mill’s product). Train tracks still run directly between the mill and some of the mill houses up to the doors of the old Edna mill in Reidsville. Mills and mill villages such as the one in Reidsville were responsible not only for changing the landscape of the south, but also its society and economy.

Archive for October, 2007

The Edna Mill and Mill Village in Reidsville, NC

October 13, 2007Letter from Peter E. Smith to his daughter Lena

October 12, 2007In the aftermath of their Civil War defeat, Southern white men faced challenges on all fronts. Economic difficulties were chief among them. The loss of slave labor and negative agricultural conditions combined with other factors to create one of the most devastating depressions in American history during the 1890’s. Formerly comfortable slave-owners now struggled to provide for their families. One of the many results was psychological anxiety felt by white males. This letter from Peter Smith to his daughter Lena on her twenty-first birthday illustrates the mental anguish fathers and husbands felt at now being able to provide.

Smith starts his letter by regretfully relaying that he is “too sad to enter in (Lena’s) festivities.” He tells her that when she was first born he looked at her and planned to give her a sum of 10,000 dollars when she turned twenty one. Twenty one years prior, Peter’s “life was all too…happy,” and he “had the brightest prospects before me; kind friends, good health, an affectionate wife, and plenty of property for a young man.” But that prosperity was not to last, and he made this clear to his daughter in writing that “after the war came the dreadful crash and loss of property…and the bright visions of your (Lena) happy future vanished like the dew before the morning sun.”

Reading this letter, one can feel the sadness and remorse of Smith, but the utter desperation and sense of failure towards the end of his letter really captures the his distress; “and I am unable to give you 10 cents instead of 10,000, I could weep tears of blood if it would avail anything.” The statement, and the letter more generally, shows that trying economic times led to feelings of self-loathing and psychological anguish.

Patrick Nerz

The Confederate Soldiers Memorial

October 12, 2007This monument to the Confederate soldiers of Rockingham County, North Carolina was funded by the Daughters of the Confederacy and was presented in 1910, less than twenty years after the end of reconstruction. The monument stands at the start of the downtown district, at the intersection of what was in 1910, two of the busiest roads in Reidsville. The memorial is not only unapologetic for the war, or the succession of North Carolina, but rather it defends these actions as acts of patriotism. The inscription’s reference to the offering of “their property and their lives” to “the altar of civil liberty” emphasizes the importance of property to confederates. By placing property before lives in the list of sacrifices’ conveys the idea that the right to property meant more to confederates than life itself.

There are numerous memorials to the confederacy and its soldiers throughout the South that have been erected in the aftermath of reconstruction as a way to honor, and in some ways attempt to validate, the legacy of the confederacy. In North Carolina, many cities have confederate memorials; notably Raleigh, the capital city, which has a memorial not only to the confederacy but also white supremacist leaders in North Carolina located in its downtown district. Also worth mentioning, Chapel Hill which has a confederate memorial on the north campus of the University of North Carolina. Interestingly enough, there have been no memorials erected in North Carolina to honor the struggles of black North Carolinians throughout slavery, reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era. The North Carolina Freedom Monument Project has recently set to work to change this misrepresentation, but the disproportionate number of confederate memorials remains testament to the adage “To the Victor Belongs the Spoils”.

Confederate Monument

October 11, 2007This is a Confederate Monument on the campus of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill in McCorkle Place known as “Silent Sam.” The monument of Silent Sam has been one of controversy both in the University and the community. It is debated whether it stands as a testimony to our past and history or only as proof of the racial aspect of history of the state and of the South. Both students and alumni of the University along with the outside organization of the United Daughters of the Confederacy supported the building of the monument, what it stood for, and used it as a way of celebrating their past and connecting it to their future.

Silent Sam is a testimony to the use of monuments, statues, and historical markers that were built during the years after the Civil War by southerners glorifying their leaders and ensuring that their side of history be known to the world and remain a permanent fixture in their environment. Members of this generation used monuments in order to build their own images and understandings of the past and how these images relate to their present life. By erecting this monument, students of the University who participated in the war are honored for their services, while at the same time, the image of the slave-holding, white supremacy South is justified and celebrated. Landscape and architecture are used in producing an image of the past that will stand long into the future in a place where all can observe.

Hannah S Hawley

Editorial Cartoon – 1898 NC Election

October 11, 2007

This political editorial cartoon published in the News and Observer on October 26, 1898 and addresses the upcoming election. The Devil corresponds to the Fusionist characteristics of the Populist and Republican Parties running against the Democratic candidate. The ballot in the voter’s hand reads “For Negro Rule.” Josephus Daniels, the owner of the paper during this time frequently used political cartoons to push for both the Democratic Party in North Carolina and for white supremacy. Norman Jennett produced this and other cartoons that were prominently featured in the newspaper during the election cycle and was given credit for his support of the Democratic Party through these means.

Beginning in 1894, the Republican and Populist parties decided to run together for political offices and to split up the offices between the two parties. This was known as “fusion.” This technique worked quite well as they were able to gain power during the 1894 and the 1896 elections. In 1898 however, the strength of the sometimes violent tactics pursued by the Democratic Party (including the production of cartoons such as this one) was able to garner enough votes to win back politics in the state. After returning to power in the state, the Democrats began working on legislation to effectively disenfranchise African Americans.

http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/1898/history.html

http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/1898/sources/cartoons/images/1026.jpg

Hannah S Hawley

Modernizing IOU’s

October 11, 2007J.A.B. Reid, the same man who traded in shoe making in 1867, by 1872 was contracting out provisions for cotton making. According to this contract, signed and sealed by William A White, Probate Judge in Warren County, NC, Reid “agrees to furnish to the said [Jim] Johnston such provision as he may need in order to make his crop – such provisions not to exceed fifty dollars ($50) in value. The said Johnston, for his part, agrees to pay for such provision on or before the first day of December 1872: and to secure the payment of said debt, he hereby gives, sells & transfers to said Reid the whole of his cotton crop or such a part thereof as shall satisfy such claim or claims as the said Reid may hold against him.”

The economy of the South was modernizing, slowly but surely. Informal, handwritten receipts were giving way to notarized contracts. Johnston was likely illiterate (he only signed his mark on the contract), and it is unknown if he was able to repay Reid, and if so, how much of the crop he harvested he was able to use for his own gain.

Reid Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Posted by Brad Proctor

An Informal Economy

October 11, 2007The economy of the South after the Civil War centered around individual, small sales between people who knew one another. J.A.B. Reid was a North Carolinian who apparently dabbled in several trades. These are two handwritten reciepts from 1867 that document payments for “shue making” – one of $12.25 and one of $6.87. There’s no explanation of the difference in price; maybe it was the quality, quantity, or type of shoes Reid made for James A Pitchford and Robert Clashon. Or maybe it was an even more informal relationship – perhaps Reid simply charged less for his services to one man as opposed to another. Regardless, these simple, handwritten receipts show a Southern economy based on relatively informal person-to-person contact.

Reid Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Posted by Brad Proctor

Store Documents from 1880’s

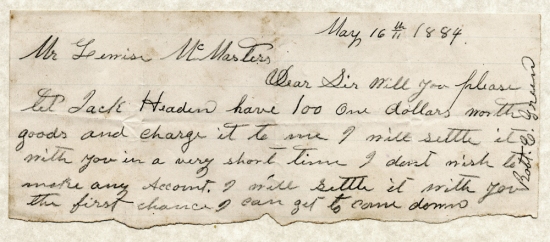

October 11, 2007Below is a store ledger, store license, and a hand written note found within that ledger from the store of William McMasters. McMasters operated his store at Sandy Creek in Randolph County, North Carolina, in the last part of the 19th century. He ran his store from a huge tract of land granted him by his father, including thousands of acres between Sandy Creek and present day Liberty, North Carolina. The store ledger is an example of similar documents from its day, detailing the items credited to the account of one Henry Allred, including such items as nails and a shovel, and the method of payment for said item, such as three days worth of work on McMasters’ own farm. The license is an official document granted to William McMasters by the sheriff of the county, granting him the permission to act as a merchant. The note is a very unique document, written to William’s son, Lewis, who helped his father run the store, from a Robert Green asking for the McMasters to grant one Jack Headen, a colored man, a dollar worth of credit on his name, to be settled by Green on a further date.

The store of William McMasters is a good example of the kinds of roles merchants played in the lives of small southern farmers in the years following the Civil War. While the majority of people in Randolph County owned their own land, merchants played a major role in the lives of tenant farmers across the South. In order to have the things required to run a farm, southern farmers needed someone to “furnish” them with needed goods, such as seeds, tools, and fertilizers. In return for goods on credit, these small farmers often signed over crop-liens, which gave the merchants a certain portion of the harvestable crop at the end of the growing season, often leaving little or nothing for the farmer to live on. As indicated by the note, this credit was often beyond the reach of African Americans, without the testimony of white community members. In this respect, merchants, like their rich planter counterparts, came to play a dominant role in the lives of small southern farmers. These merchants became powerful and prestigious members of their communities, bringing new material goods to the agricultural regions of the South. In this way they helped transform the South from its antebellum barter economy into a modern, market-based world.

Posted by Tristan Routh

Signed Oath of Allegiance by Ex-Confederate Soldier

October 11, 2007This document is an oath if allegiance signed by Stokes A. Hopkins in June of 1865. Stokes Hopkins was a native of the southwestern portion of Randolph County, North Carolina. He served in the 38th North Carolina with the Army of Northern Virginia from November of 1861 until his capture by Union troops in March of 1865 at Petersburg, Virginia, shortly before the surrender of Confederate forces at Appomattox. After his capture he was sent to a Union P.O.W. camp at Point Lookout, Maryland, where he remained until his release the following June. Like many of his former comrades-in-arms he was then forced to make the trek home on foot. The world into which these veterans emerged was a new world, where everything they had ever known to be true had suddenly shifted. These veterans would have to learn to cope with this new world, as well as the memory of their defeat.

This document is indicative of the steps taken following the Civil War to mend a nation divided. The South had to be somehow reinstated into the Union on terms that were acceptable to both the victorious North and the recently defeated and chastised South. If the country was to ever mend itself this process would need to be carried out with as little strife and ill-feeling as possible. The nation was to be whole again, and these oaths taken by ex-Confederates were some of the first measures taken by the U.S. government to bring southerners back into the fold. This oath was made possible by the broad amnesty that President Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Abraham Lincoln after his assassination, granted on May 29th 1865. This sweeping pardon essentially forgave southerners who had rebelled against the Union, and restored all of their former rights, save that of the right to own slaves. This oath of allegiance was the document, whose signing was required for the granting of this pardon. Johnson allowed most ex-Confederates to sign this oath, with the only exception being high-ranking officers and state officials, and all individuals with taxable property worth $20,000 or more. This move was an attempt by Johnson to restore the rights of the most important part of the ex-Confederacy, the common soldier.

Posted by Tristan Routh

1866 Cartoon

October 10, 2007Cartoon from the book “America’s Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War” by Eric Foner and Olivia Mahoney. This racist cartoon played upon the fears that white men had, that government assistance would benefit freedman at the expense of white workers. This cartoon originally came from a campaign from Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial campaign of 1866.

Jessica Pate